-

Name of property current (historical)

-

Mies van der Rohe Residential District, Lafayette Park

-

Entry author

-

Alex Burgaud

-

Abstract

-

The Mies van der Rohe Residential District is located in Lafayette Park, situated just east of the city of Detroit. Designed by its principal namesake, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the community was finally commissioned in 1956 after years of delays in development due to insufficient funds or a lack of developers whose visions aligned with those of the neighborhood. This gift opened up in phases throughout the late 1950s to early 1960s during which it switched hands between developers due to a tragedy that prevented Mies’ plan from reaching its full potential.

During a time in American history immediately post-war, this gift did not unwrap without controversy. Sitting on the soil that once sat the houses of the Black Bottom neighborhood, Lafayette Park was one of many births of the urban renewal movement. Defined by the erasure of what cities defined as “slums”, Black Bottom was just one of the many communities around the United States that were razed to make way for urban housing to bring people back into city living. Although this gift is historical and diverse today, it not only gentrified an already diverse community but it led to the success of other urban renewal projects around the country.

-

Address

-

1301 Orleans St, Detroit, MI 48207

-

Architect

-

The district was designed by German-born Ludwig Mies van der Rohe whose firm was originally based in Europe before moving to America in the 1930s. To assist him on this project, he brought along Ludwig Hilberseimer (site planner) and Alfred Caldwell (landscape architect).

-

Date (comission)

-

It was commissioned some time between 1955 to 1956.

-

Date (completion)

-

It was completed in stages between 1959 to 1964.

-

Program/ function

-

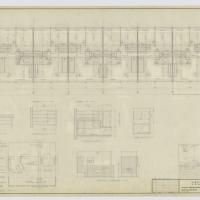

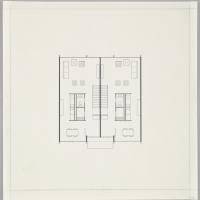

The Pavilion:

Opened in 1956, this building has always functioned as a foundation for many residential units.

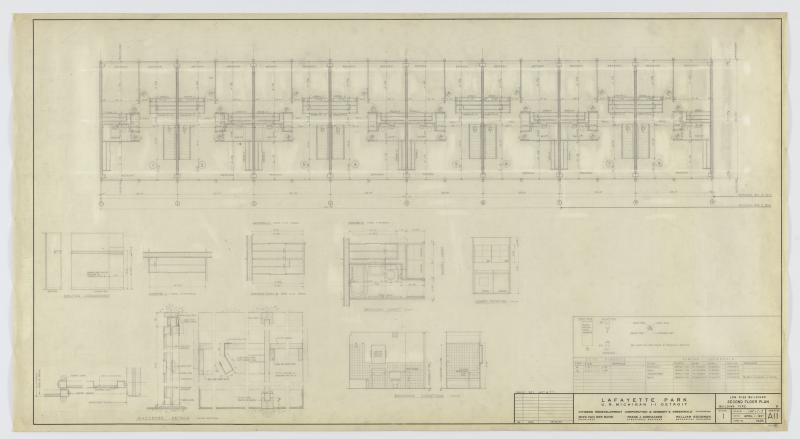

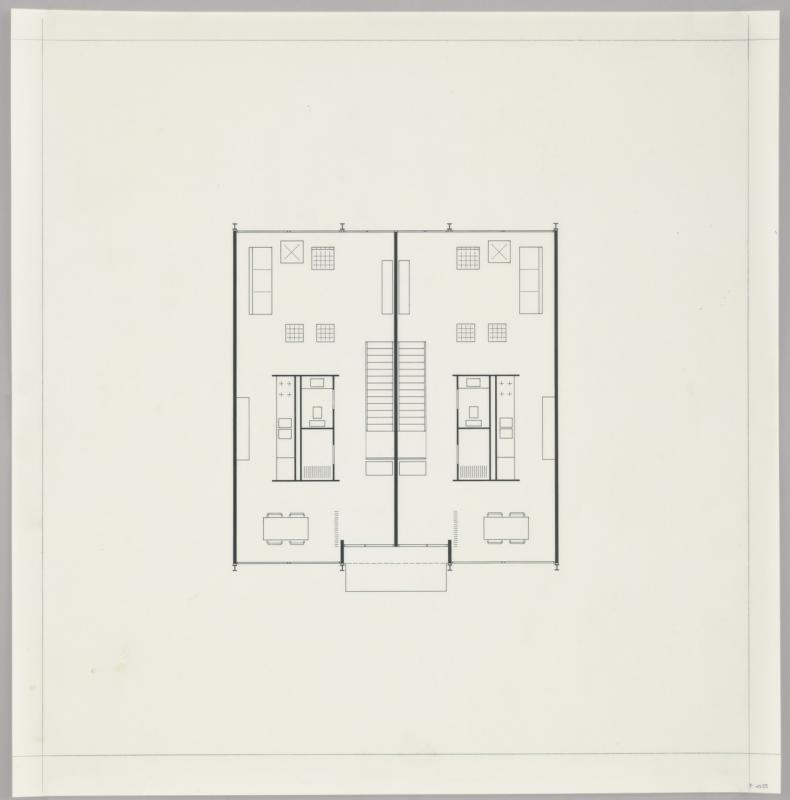

Townhouses and Courthouses:

These buildings opened as apartments and remained that way until 1961-1962 after which they were converted into their original purpose as co-operatives. Two units were used as a school until the opening of the nearby Chrysler Elementary in 1963.

Lafayette Towers (West and East):

These buildings have always functioned as a foundation for many residential units.

-

Contractor

-

No information found

-

Date (modification, adaptation, renovation)

-

1971: Carlton Apartments added

1974: Palms East Apartments added

2016: DuCharmePlace added

2023: Lafayette-West added

-

Style/ distinct features/ cultural reference

-

International Style

-

Gift giver/ funder/ contributor

-

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created in 1934 by the United States Congress following the enactment of the National Housing Act of that year to provide American citizens with mortgage insurance to prevent losses.

As part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal, the Housing Act of 1949 was enacted to gift urban housing following the exodus of people living in city centers to the suburbs where the jobs were (ex. Detroit and the Motor City). It was also there to gift homes for every American family, especially since around that time, the United States was a nation of renters (1 in 10 owned a house).

-

Beneficiaries and impact on the community

-

Beneficiaries included the city of Detroit which was determined to bring in more housing and persuade people to move back from the suburbs to the urban core. In addition, federal, local, and state governments wanted to use the increase in housing as a way to also increase tax revenue to fund essential services.

This project contributed to the destruction of Black Bottom, the center of Detroit’s African-American population, and subsequently displaced residents to the north and west of the city. However, its success led to increased tax revenue and Detroit pursuing similar projects in Corktown and other areas (urban renewal zones).

-

Was it part of a network of buildings?

-

Mies’ buildings are part of a vast plan of several other projects from other architects that together compose the district.

-

Sustainability (financial, cultural)

-

Increased tax revenues resulting from the construction of the project led to financial sustainability for all levels of government.

The urban renewal zone first took away before bringing back cultural sustainability. The removal of Black Bottom was a negative effect as it displaced people from various backgrounds, but the introduction of wealthy people in the district helped bring out a positive appearance. This is also known as gentrification.

-

Size/ scale

-

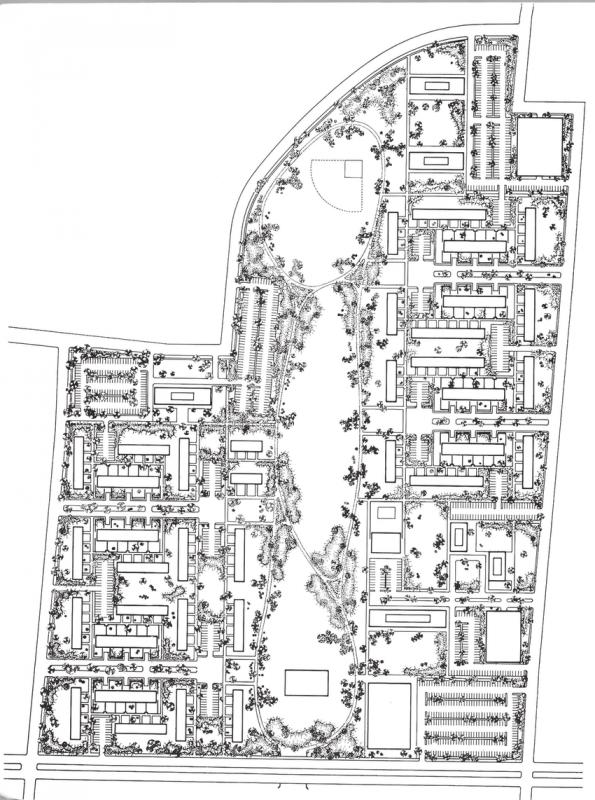

46 acres (19 hectares) for the district.

129 acres for the entirety of Lafayette Park.

-

Was the community involved in the process?

-

The African-American community had no say in the process as most projects that were created following the Housing Act of 1949 directly impacted their neighborhoods that were deemed to be "slums".

-

Q1: What were the motivations of the gift-giver and the implications of the gift for the community ?

-

Stemming from the conclusion of the Second World War, the superblocks combine both low- and high-density housing, a move favored by the Federal Housing Administration. According to Newsweek, “These urban renewal programs needed to appeal to upper- and middle-class residents who had, up to that point, been leaving the city for the suburbs” (Newsweek 2015). The city of Detroit fit this criterion and sought to create a diverse community that would entice the suburban people to come back, becoming one of the first American cities to take action. The other reason that further motivated the pursual of urban renewal was that Detroit had no more land available for development. As a result, that limited property tax revenue.

The main implication of the gift for the community was that it would benefit some and disregard others. Ironically, the gift wiped out the diverse Black Bottom, a neighborhood that was composed mostly of blacks, but also of Eastern European immigrants (Detroit Historical Society, n.d.). This move caused all of the inhabitants to be rehoused all across Detroit. Even though Black Bottom was completely destroyed, there are still close ties to remnants of the black community as there are churches still standing that serve as gathering places.

In architectural terms, Lafayette Park was introduced based on the “superblock” idea combined with a modern design aesthetic courtesy of Mies (Stanard n.d., 37). This meant that the design was focused on erasing the normative city grid of streets and how both the interior and exterior interacted with sunlight to ensure maximum efficiency. As a result, much of the neighborhood was simply connected by sidewalks that weaved in and out of the landscape creating a self-contained community. This shows how the motivations of the gift-givers were planned all along when the neighborhood was initially planned for longevity.

-

Q3: Do the design characteristics (i.e material, layout, location) reflect either the culture of the giver, the culture of the receiver, or a mixture of both?

-

While the International style was not fully grasped by the American people until, after the Second World War, the most well-known portions of the district were designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a modernist proponent of the style. With a focus on social issues and technological advances at the start of the 20th century, the style initially could only be found in Europe. Moving away from wood, stone, and brick, the exposed steel beams found in this style carry the weight of the structure. This showed how Mies emphasized his belief that the building must be a clear expression of its structure and reflect the modern technology of its time (Chen, n.d.)

The layout of the district was carefully laid out by Ludwig Hilberseimer and Alfred Caldwell who sought to maintain a natural landscape and create an integrated community that would bring people back to "the heart of the city" (Detroit Historical Society, n.d.). It was Hilberseimer who was particularly focused on the social consequences of his work and how it would affect the people living in it. This led to him envisioning the city as a “decentralized suburb”. His colleague Caldwell was equally concerned about the definition of urban renewal projects and advocated for green space and strict zoning to juxtapose industry and residential. Since the two shared such similar ideals, this ushered in their ideal “suburb in the city”.

These reasons are why I attribute the design characteristics of the residential district indirectly to the giver. Although the giver of the district was assigned by the Federal Housing Administration, it was Mies and his team who designed the bulk of it. According to biographer Franz Schulze, Lafayette Park was the closest that “Mies ever designed to a realization of his ideas of modern architecture in the service of modern American city living” (Schulze 292).

-

Q4: To what extent did the gift-giving process shift away from the original timeline due to financial and/or social issues associated between the giver and receiver?

-

The idea behind Lafayette Park began in 1946 before the Housing Act when the city of Detroit began acquiring overcrowded slum properties for redevelopment. Their original plan, known as the Gratiot Redevelopment Project, was to clear the land before reselling it to developers to construct low- and middle-income housing (Leclair 1955, 1-2). It is believed that the Federal Housing Administration and the city had intended to gift this district as soon as possible. Until 1952, developers came and went as they were cautious of Detroit’s redevelopment plan and believed that no middle-income families would ever move to the area. Because of this, the original plan fell through.

In 1954, Walter Reuther, the president of the United Auto Workers, finally applied public pressure on the city to proceed with the project. This move led to the appointment of a citizen’s committee to take over the project and eventually more support for the betterment of housing for all people. After years of struggling, the community began searching for designers to start drawing up plans, including Oscar Stonorov, who specialized in “socially responsible” housing developments (Herrington 2015). Although Stonorov’s plan did not follow through, it was the first step towards utilizing the International Style for the campus.

In 1956, the committee selected Herbert Greenwald, a real estate developer from Chicago to take on the project with a focus on middle-income families. He had hired Mies van der Rohe on several occasions in the past for his other residential projects primarily in his city of origin. The plan changed many times throughout their involvement and took its biggest hit when Greenwald perished in a plane crash in 1959 (Mies Detroit, n.d.). Additionally, the recession of 1958 led to the firing of more than half of the staff on the project, and was left to a different developer to finish it.

-

Bibliography

-

Chen, Joseph. n.d. "Ludwig Mies van der Rohe." Accessed April 22, 2023. http://www.people.vcu.edu/~djbromle/modern-art/02/Ludwig-Mies-van-der-Rohe/index.htm

Detroit Historical Society. n.d. "Black Bottom Neighborhood." Accessed April 9, 2023. https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/black-bottom-neighborhood

Detroit Historical Society. n.d. "Mies van der Rohe Residential District, Lafayette Park." Accessed April 9, 2023. https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/mies-van-der-rohe-residential-district-lafayette-park

Herrington, Susan. 2015. "Fraternally Yours: The Union Architecture of Oskar Stonorov and Walter Reuther*." Social History. Vol. 40, No. 3. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Leclair, Richard. 1955. "A Case Study of the Gratiot Redevelopment Project." Thesis, Wayne State University.

Mies Detroit. n.d. "Design." Accessed April 9, 2023. https://www.miesdetroit.org/filter/exhibition/Design

Newsweek. 2015. "Does Lafayette Park's Landmark Status Whitewash History?" Accessed April 22, 2023. https://www.newsweek.com/does-lafayette-parks-landmark-status-whitewash-history-367320

Schulze, Franz. 1986. Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Stanard, Virginia. n.d. "Lafayette Park: In-Between Urbanism." Accessed April 22, 2023. https://www.acsa-arch.org/chapter/lafayette-park-in-between-urbanism/